When will the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies collide?

EarthSky in SPACE | February 8, 2019

The Andromeda galaxy is the nearest large spiral to our Milky Way. Astronomers have suspected for some time it will eventually collide with our Milky Way. Now – thanks to the Gaia satellite – they know more.

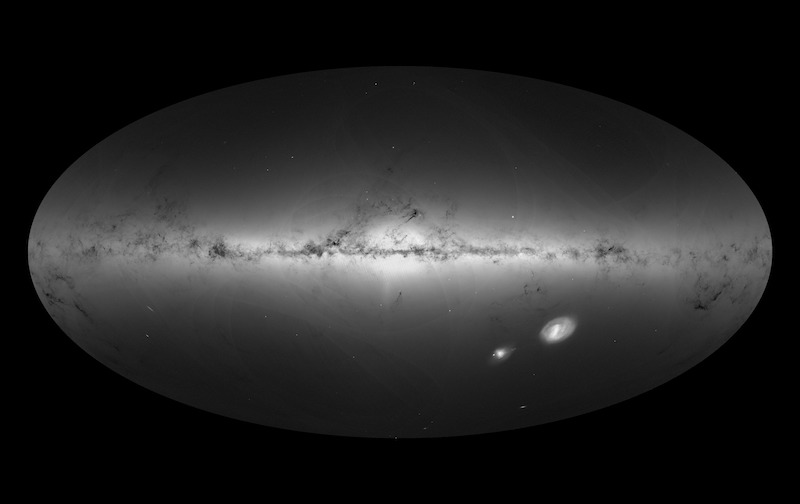

| An all-sky view of our Milky Way galaxy and neighboring galaxies, based on measurements of nearly 1.7 billion stars in Gaia’s 2nd data release. The map shows the density of stars observed by Gaia in each portion of the sky from July 2014 to May 2016. Image via ESA/Gaia/DPAC |

The first surprise is a new estimate for when the collision will occur. Astronomers thought it would happen some 3.9 billion years from now. But the astronomers who studied Gaia’s data said they now believe it’ll happen 600 million years later than previously estimated, perhaps 4.5 billion years from now. What’s more, they said, the Andromeda galaxy is:

… likely to deliver more of a glancing blow to the Milky Way than a head-on collision.

These results were published February 7 in the peer-reviewed Astrophysical Journal. Astronomer Roeland van der Marel of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore – who led the study – commented:

We needed to explore the galaxies’ motions in 3D to uncover how they have grown and evolved, and what creates and influences their features and behavior.

We were able to do this using the second package of high-quality data released by Gaia.

Gaia does what is called astrometry. Its job is to scan the sky repeatedly, observing each of its targeted billion-plus stars an average of 70 times over its five-year mission. Again and again and again, Gaia will acquire data points on the positions of stars in the Milky Way, and now in the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies, too. We know that stars move through space. Gaia will tell us, exactly, how they moved during that five-year period.

It may not sound very dramatic. But it is. That much knowledge about star motions – actual data on the motions of more than a billion stars – is unprecedented in the history of astronomy. That is why there have been so many astounding discoveries from Gaia already.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote